Throughout his ministry, Spurgeon was a champion of Baptist associationalism. While he believed in the congregational autonomy of each local church, Spurgeon gladly partnered with other Baptist churches for the cause of missions, evangelism, and church planting. So he reinvigorated the London Baptist Association, often hosting and chairing meetings. He became active in the Baptist Union, contributing to its growth throughout the 19th century. His church also supported and sent out workers through numerous evangelistic and missionary societies. This kind of associationalism would carry on throughout his ministry. But in the Downgrade Controversy, all of that would seemingly change.

In the Downgrade Controversy, Spurgeon took a stand in the Baptist Union against the infiltration of a new kind of theology. Advocates of this theology claimed to be teaching an updated, modern version of Christianity. But Spurgeon believed they were teaching an entirely different religion.

A new religion has been initiated, which is no more Christianity than chalk is cheese; and this religion, being destitute of moral honesty, palms itself off as the old faith with slight improvements, and on this plea usurps pulpits which were erected for gospel preaching. The Atonement is scouted, the inspiration of Scripture is derided, the Holy Spirit is degraded into an influence, the punishment of sin is turned into fiction, and the resurrection into a myth, and yet these enemies of our faith expect us to call them brethren, and maintain a confederacy with them!

While some evangelicals felt that they could continue to work with such people, Spurgeon believed that to remain in association with them was to compromise the gospel. After all, how could churches work together for evangelism, missions, and church planting when they didn’t even agree on the gospel? On October 1887, Spurgeon resigned from the Baptist Union, and he would soon also resign from the London Baptist Association and all other associations that had no clear evangelical statement of faith. For this, Spurgeon would be publicly rebuked by the Baptist Union, and many of his friends would turn on him. This event proved to be one of the greatest heartaches of his life. Though some hoped for restoration, his breach with the Baptist Union was never healed.

In retelling the story of the Downgrade Controversy, some have argued that Spurgeon entirely gave up on all formal associations. R. J. Sheehan writes, “Spurgeon saw the way ahead as an informal alliance of those separatists that desired fellowship. Nothing organized or formal was desired or envisaged.” Additionally, such informal associations “[should not be] limited to one strand of evangelical thought.” [1] In other words, according to Sheehan, Spurgeon believed that if any associations were to exist, they should be informal, and they should not focus on second-tier distinctives (i.e. baptism, church government, etc…), but only on gospel orthodoxy.

But was this really Spurgeon’s position?

The Fraternal Union

Sheehan gives evidence of such a position in the formation of a pastors’ fraternal in London after the Downgrade Controversy.[2] Led by Spurgeon and Archibald Brown, seven evangelical pastors began to meet together for mutual encouragement, prayer, Bible study, and fellowship. Over time, they would invite other like-minded pastors across all denominations to join their group, so that eventually, 30 pastors belonged to this fraternal.

However, these pastors were not content to merely leave this as an informal gathering. They decided to go public and articulate their convictions. In 1891, they released the following confession of faith:

We, the undersigned, banded together in Fraternal Union, observing with growing pain and sorrow the loosening hold of many upon the Truths of Revelation, are constrained to avow our firmest belief in the Verbal Inspiration of all Holy Scripture as originally given. To us, the Bible does not merely contain the Word of God, but is the Word of God. From beginning to end, we accept it, believe it, and continue to preach it. To us, the Old Testament is no less inspired than the New. The Book is an organic whole. Reverence for the New Testament accompanied by scepticism as to the Old appears to us absurd. The two must stand or fall together. We accept Christ’s own verdict concerning “Moses and all the prophets” in preference to any of the supposed discoveries of so-called higher criticism.

We hold and maintain the truths generally known as “the doctrines of grace.” The Electing Love of God the Father, the Propitiatory and Substitutionary Sacrifice of his Son, Jesus Christ, Regeneration by the Holy Ghost, the Imputation of Christ’s Righteousness, the Justification of the sinner (once for all) by faith, his walk in newness of life and growth in grace by the active indwelling of the Holy Ghost, and the Priestly Inter cession of our Lord Jesus, as also the hopeless perdition of all who reject the Saviour, according to the words of the Lord in Matt. xxv. 46, “These shall go away into eternal punishment,”—are, in our judgment, revealed and fundamental truths.

Our hope is the Personal Pre-millennial Return of the Lord Jesus in glory.

This confession was published in the newspapers (with no small controversy) as a public declaration to the world that historic Christianity had not yet died, but was still being held by pastors throughout the city. Sheehan cites the example of the Fraternal Union as an example of an informal association. Yet, this group was formal enough to release a public confession of faith and to closely limit her membership to those who held to it.

The Surrey and Middlesex Association

After leaving the Baptist Union, people asked Spurgeon if he would ever consider joining another Baptist association. Spurgeon made it clear that he would not join any that was still connected to the Baptist Union. But by the summer of 1888, Spurgeon learned that the Surrey and Middlesex Association was also planning on leaving the Baptist Union. Writing to a friend, Spurgeon confided that he would “probably unite with it.” He was encouraged to know that “this will be an Association outside of the Union, sound in doctrine.” In this regional association, Spurgeon had hopes that it would be “the nucleus of a fresh Union,” drawing more theologically like-minded churches together.

Eventually, the Surrey and Middlesex Association did leave the Baptist Union, and on October 30, 1888, Spurgeon applied for membership, “I feel that I can endorse your principles… I apply for personal membership with you on the belief that you are not a part of the Baptist Union.”

In addition to not being a part of the Union, the association had a robust evangelical statement of faith.

Surrey and Middlesex Statement of Faith

Declaration

That among the truths believed and held by the Churches comprising this Association, the following are entitled to special enumeration:

1. The Divine inspiration of the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments and their absolute sufficiency as the only authorized guide in matters of religion.

2. The existence of three equal persons in the Godhead – the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

3. Eternal and personal election to holiness here, and eternal life hereafter.

4. The depraved and lost state of mankind.

5. The atoning efficacy and vicarious nature of the death of Christ.

6. Free justification by his imputed righteousness. The necessity and efficacy of the work of the Holy Spirit in conversion and sanctification.

7. The final preservation of the saints.

8. The duty of all men to whom the Gospel is made known to believe and receive it.

9. The spirituality of the Kingdom of Christ, and His supreme authority as sole Head of the Church.

10. The resurrection of the dead, both the just and the unjust.

11. The general judgment.

12. The eternal happiness of the righteous, and the eternal misery of such as die impenitent.

On May 5, 1889, Spurgeon would also lead the Metropolitan Tabernacle in joining the Surrey and Middlesex Association. With Spurgeon presiding, the church minutes record that Deacon Buswell made the case that “in the interest of the Church, as [a] source of strength to the Association, this Church should be affiliated.” So the congregation passed the following resolution: “Resolved: that this Church do apply for admission to the Surrey and Middlesex Association.” In one sense, the Metropolitan Tabernacle did not need an association. She was a mega-church and had resources for every kind of ministry that was needed. And yet, the church was convinced that she did not exist only for her own prosperity, but also to see other churches strengthened. Joining this Baptist association would allow the Metropolitan Tabernacle to be a “source of strength” for other gospel-preaching Baptist churches.

Later that spring, Spurgeon would speak at the Surrey and Middlesex Associational meeting on May 21, 1889, and at that meeting, he and his church would be elected members. He would speak again at the Associational meeting in 1890, drawing large crowds and new applicants to the association. Though his time in the Association was brief, he was able to strengthen their work during this critical period, and the Metropolitan Tabernacle would continue to be involved after his passing.

The Pastors’ College Evangelical Association

Throughout his life, Spurgeon had invested in the Pastors’ College, not only training men but building a network of like-minded, Baptist pastors and churches. But this network would also be rocked by the events of the Downgrade Controversy.

In the spring of 1888, Spurgeon presented a new Declaration of Faith to the graduates of the Pastors’ College. At their annual meeting, he resigned his office as the president of the Pastors’ College Conference and sought to reform their conference as the Pastors’ College Evangelical Association, under the new Declaration of Faith. This declaration stated:

We, as a body of men, believe in the “doctrine of grace,’ what are popularly styled Calvinistic views (though we by no means bind ourselves to the teaching of Calvin, or any other uninspired man), but we do not regard as vital to our fellowship any exact agreement upon all the disputed points of any system, yet we feel that we could not receive into this our union any who do not unfeignedly believe that salvation is all of the free grace of God from first to last, and is not according to human merit, but by the undeserved favour of God. We believe in the eternal purpose of the Father, the finished redemption of the Son, and the effectual work of the Holy Ghost.

1. The Divine inspiration, authority, and sufficiency of the Holy Scriptures.

2. The right and duty of private judgment in the interpretation of the Holy Scriptures, and the need of the teaching of the Holy Spirit, to a true and spiritual understanding of them.

3. The unity of the Godhead and the Trinity of the persons therein, namely, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

4. The true and proper Godhead of our Lord Jesus, and his real and perfect manhood.

5. The utter depravity of human nature in consequence of the Fall, which Fall is no fable nor metaphor, but a literal and sadly practical fact.

6. The substitutionary sacrifice of the Lord Jesus Christ, by which alone sin is taken away, and sinners are saved.

7. The offices of our Lord as Prophet, Priest and King, and as the one Mediator between God and man.

8. The justification of the sinner by faith alone, through the blood and righteousness of the Lord, Jesus Christ.

9. The work of the Holy Spirit in the regeneration, conversion, sanctification, and preservation of the saved.

10. The immortality of the soul, the resurrection of the body, and the judgment of the world by our Lord Jesus, which judgment will be final, according to the words of the Great Judge: “These shall go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.”

11. The Divine institution of the Christian ministry, and the obligation and perpetuity of the ordinances of Believers’ Baptism and the Lord’s Supper.

We utterly abhor the idea of a new Gospel or an additional revelation, or a shifting rule of faith to be adapted to the ever-changing spirit of the age. In particular we assert that the notion of probation after death, and the ultimate restitution of condemned spirits, is so unscriptural and un-protestant and so unknown to all Baptist Confessions of Faith, and draws with it such consequences, that we are bound to condemn it, and to regard it one with which we can hold no fellowship.

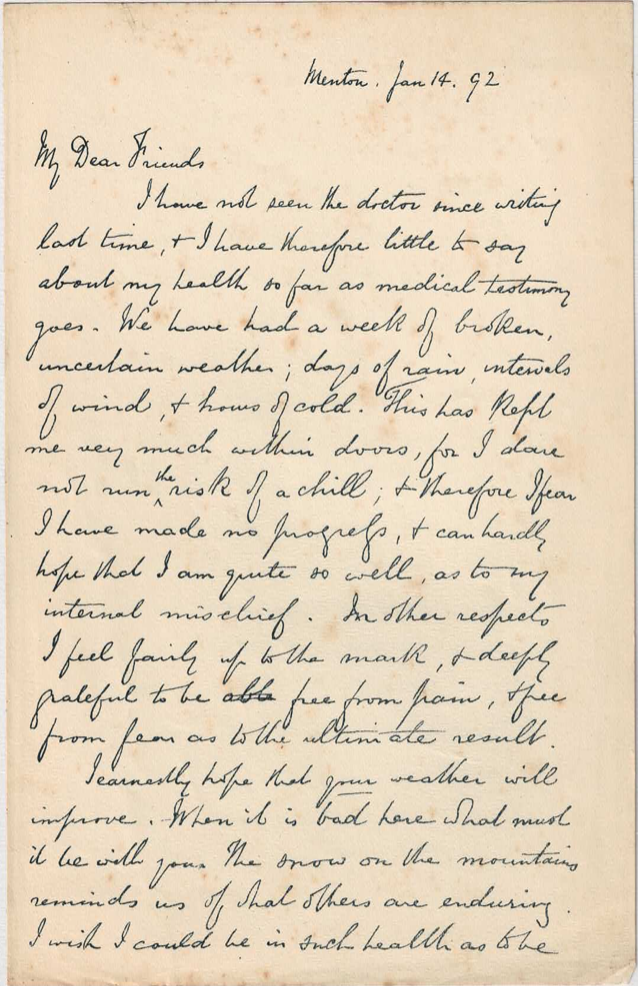

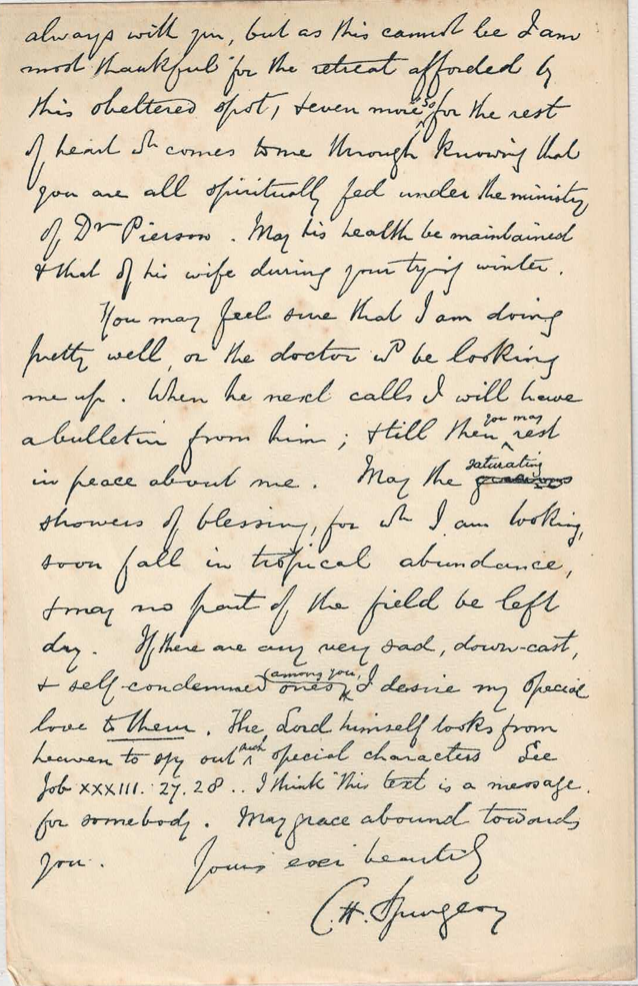

The vote for this new declaration and the new formation of the Pastors’ College Evangelical Association was 432 out of 496. This was a clear victory, but not without controversy. The ‘Nays’ continue to voice their protest and threatened to force their way into the membership. As the year went on, Spurgeon would learn of more defections. At least 80 of his men rejected the declaration and supported the Baptist Union. Spurgeon wrote to a friend, “I have been sorely wounded and thought I would quite break down, but the Lord has revived me and I shall yet see his truth victorious. I cannot tell you by letter what I have endured in the desertion of my own men. Ah me! Yet the Lord liveth, and blessed be my rock.”

Despite these heartaches, the Pastors’ College network would continue through the newly formed Pastors’ College Evangelical Association. As an association working for church planting and pastoral training, it was important to affirm not only primary gospel doctrines (articles 1-10) but also secondary ecclesiological convictions (article 11). Amid the battle for gospel fidelity, Spurgeon believed that the work of training pastors and planting healthy churches was vital for the defense and advancement of the gospel.

We, being assured of the gospel, go on to prove its working character. More than ever must we cause the light of the Word to shine forth… If sinners are converted…, and the churches are maintained in purity, unity, and zeal, evangelical principles will be supplied with their best arguments. A ministry which, year by year, builds up a living church, and arms it with a complete array of evangelistic and benevolent institutions, will do more by way of apology for the gospel than the most learned pens, or the most labored orations.[3]

Conclusion

As Lewis Drummond writes, following the events of the Downgrade Controversy, “Spurgeon and his Metropolitan Tabernacle were not Independent Baptists, as some would like to emphasize.”[4] It is true that Spurgeon did not join another Baptist association right away after his resignation from the Baptist Union in 1887. Even as others asked him about this, he waited to see how this controversy would play out. But as the leader of the Pastors’ College Conference, he reformed that association in the spring of 1888 under clear evangelical convictions. One would think that such an association would have been sufficient. But Spurgeon wanted to be involved with Baptists beyond his own circles. So, in 1889, he and his church joined the Surrey and Middlesex Association, seeking to strengthen the hand of Baptists throughout the region.

Even after the Downgrade Controversy, Spurgeon clearly remained committed to Baptist associationalism. What changed, however, was his conviction that all such associations require a confessional basis, the affirmation of a clearly articulated, evangelical declaration of faith as the basis for membership in the association – from regional Baptist associations to church-planting or pastoral training institutions, all the way down to a pastors’ fraternal. The importance of this lesson remains for our day.

[1] R. J. Sheehan, C. H. Spurgeon and the Modern Church, 120-121. Many thanks to Andrew King for pointing this out to me. To learn more about his work to promote gospel-centered Baptist associations in the UK, see https://gracebaptists.org/.

[2] S&T 1891: 446-447.

[3] S&T 1890:3.

[4] Lewis Drummond, Spurgeon, 708-711.