Introduction

The 19th century was an age of empire for the Victorians, not only over the kingdoms of men but also over the animal kingdom. Animals were an indispensable part of everyday life. Even as people left the countryside for the city, animals continued to play an integral role in society. As cities expanded and the city population grew, more horses and other beasts of burden were needed to transport goods and passengers.[1] It would not have been unusual to find cows, goats, and other farm animals in urban areas, bringing unsanitary conditions with them.

Beyond these more common relationships, Victorians also viewed animals with fascination. Domestic pets grew fashionable among all classes, including birds, dogs, cats, and even more exotic animals like monkeys and ferrets. As Britain’s empire expanded, animals from all over the world were brought back to England for public entertainment, leading to the rise of zoos and circuses. The first live hippopotamus in Europe arrived in London in 1850 and became the star attraction of the Surrey Zoological Gardens.[2] By the early 20th century, rather than simply locking animals in an iron cage, they were placed in exhibits that mimicked their original landscapes. These landscapes were still made out of painted concrete, wood, and metal, but the Victorians much preferred to “see captive animals and believe that they [were] somehow happy.”[3]

Animals played an important part in the Victorian economy. Birds, for example, became a booming industry. Even as hunters and collectors pursued exotic specimens for study and sale among the upper-class, the rearing of canaries and nightingales became a domestic industry that could generate a significant income for a lower-class family. This trend spilled over into the world of fashion, where bird feathers and animal skins in women’s hats and clothing became all the rage. Some estimate nearly 40 million pounds of plumage and bird skins imported into the U.K. between 1870 and 1920, an industry worth more than £20m a year at its peak.[4]

Victorian dominance over the animal world was also expressed in animal cruelty. With the rise of modernization, working animals were treated less as living creatures and more as machines to be driven to the ground. [5] Scientific and medical experimentation on animals grew without regard to their suffering.[6] In the entertainment industry, animals continued to be used in all kinds of violent competitions, including shooting matches and cage fights. Such attitudes towards animals filtered down to the general population. From the cab driver who flogged his horses, to the farmer who starved his oxen, to children torturing small creatures for entertainment in an alleyway, cruelty towards animals was widespread in Victorian society.

Alongside these instances of dominion over the animal kingdom, Victorians also developed a concern for animal welfare. With the publication of The Origin of Species in 1859 and The Descent of Man in 1871, Charles Darwin presented an indissoluble link between humanity and the animal world, claiming that “there is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties.”[7] With this new understanding of humanity’s origins came a growing concern for the humane treatment of animals. Legislation and various societies were established to protest and work against animal cruelty. Literary works like Black Beauty presented animals as heroic and noble, even human, under terrible suffering.[8] Beginning in 1860 with the Battersea Dogs’ and Cats’ Home, the first animal shelter was established to care for the large population of stray dogs and cats. Eventually, Battersea would have the support of Queen Victoria as its patron.[9]

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892) ministered in the heart of the Victorian empire amid the complexities of his society’s relationship with animals. As one historian observed, though Spurgeon was “a man behind his time” in his theology, he was also “a man of his time,” as a Victorian shaped by his cultural context.[10] This dynamic can be seen in Spurgeon’s teaching on animals throughout his life. This paper will demonstrate that, while reflecting his Victorian values, Spurgeon viewed the animal world (and all of nature) as a “symbol of the invisible,” working alongside Scriptural revelation to illustrate and reinforce biblical truths.[11] It will first explore Spurgeon’s personal interaction with animals, then consider his teaching on the animal world.

Spurgeon and the Animal World

Growing up in the village of Stambourne in his grandfather’s manse, animals were a part of everyday life. The family owned a small dairy at the back of the house, which “was by no means a bad place for a cheesecake, or for a drink of cool milk.” [12] Next to the house was a small garden, where Spurgeon would often see his grandfather walking in preparation for his sermons. Though Spurgeon grew up around horses, his favorite was the one in his grandfather’s house. “In the hall stood the child’s rocking-horse… This was the only horse that I ever enjoyed riding.”[13] Even at a young age, Spurgeon was not much of an athlete. He preferred studying books to playing sports and riding horses. However, growing up in the countryside, he loved nature and the outdoors.

As a teenage student, his education involved the study of the animal world. Among the early sermon notebooks kept at Spurgeon’s College, U.K. is a notebook entitled “Notes on the Vertebrate Animals Class Aves.” This incomplete notebook contains Spurgeon’s research, likely as a teenager, on 32 species of birds.[14] He repeatedly cites Georges Cuvier, whose theory of animal development based on natural cataclysms would provide an alternative to Darwin’s theory of natural selection.[15] The notebook is not limited to domestic birds but contains research on birds from all over the British empire, including peacocks, parrots, and penguins. As discoveries were being made in the animal world, these discoveries were published back home, and they shaped the imagination of young students all over England.

After a short but successful pastorate in the agricultural village of Waterbeach, Spurgeon moved to London to be the pastor of the New Park Street Chapel in 1854. The church was located in Southwark, “near the enormous breweries of Messrs. Barclay and Perkins, the vinegar factories of Mr. Potts, and several large boiler works… the region was dim, dirty, and destitute, and frequently flooded by the river at high tides.”[16] The industrial revolution was in full swing in London. Coming from Waterbeach, the pollution and the pressures of city life would have been a difficult adjustment.

Like other busy Londoners, Spurgeon owned a horse and carriage, which he considered “almost absolute necessaries” given his many preaching engagements.[17] However, his interaction with the animal world in London extended beyond mere transportation. In 1857, Spurgeon and his wife, Susannah, purchased a home on Nightingale Lane, Clapham. At that time, it was still “a pretty and rural, but comparatively unknown region.” Amid the growing pressures of pastoral ministry and public attention, his home became a place of seclusion and rest. Susannah recalls, “we could walk abroad, too, in those days, in the leafy lanes, without fear of being accosted by too many people.”[18]

Though the house itself was awkwardly configured, it came with a large garden that made up for any inconveniences. The couple “had the happy task of bringing it gradually into accord with our ideas of what a garden should be.”[19] In addition to cultivating flowers and plants, the Spurgeons turned their yard into a bird sanctuary. On summer afternoons, Susannah would lay out a blanket in the yard filled with birdseed so that the birds might come feast.[20] Amid the busyness of his ministry, Spurgeon found refreshment and renewal in his garden.

When I go into my garden I have a choir around me in the trees. They do not wear surplices, for their song is not artificial and official. Some of them are clothed in glossy black, but they sing like little angels; they sing the sun up, and wake me at break of day; and they warble on till the last red ray of the sun has departed, still singing out from bush and tree the praises of their God.[21]

Though he appreciated the attractions and exhibits of the city, Spurgeon found consistent refreshment in the pleasures of nature. His delight in these birds was not driven by scientific curiosity but a spiritual enjoyment, leading him in praise to God like a church choir. Visitors also noted his fondness for animals. When the Jubilee Singers visited the Spurgeons in 1874, they observed, “We had no sooner entered than he called our attention to the exploits of an enormous cat which sprang through his arms with the agility of a trained athlete; we found, also, that his grounds were rich in birds and domestic animals, for which he and Mrs. Spurgeon have great fondness.”[22] These animals were Spurgeon’s companions in his home, and he introduced them to his guests as one would introduce any other family member.

As the years wore on in London, the pollution worsened. Nightingale Lane soon grew more crowded, and the smoke and fog of London settled there for much of the year, making his garden less of a retreat. As Spurgeon’s health declined, he had to take longer and longer trips to Mentone, France, to recover his health in the warm climate and fresh air. So, in the summer of 1880, when the opportunity arose to purchase the Westwood estate, situated on Beulah Hill above the fog, Spurgeon saw this as God’s kind providence. The large, nine-acre residence came complete with “grass-bordered walks around the house,… a winding pathway sheltered by overhanging trees,… a little rustic bridge, and… a miniature lake.”[23] This estate became a place for ministry, where Spurgeon could gather with his students and meet with visitors.

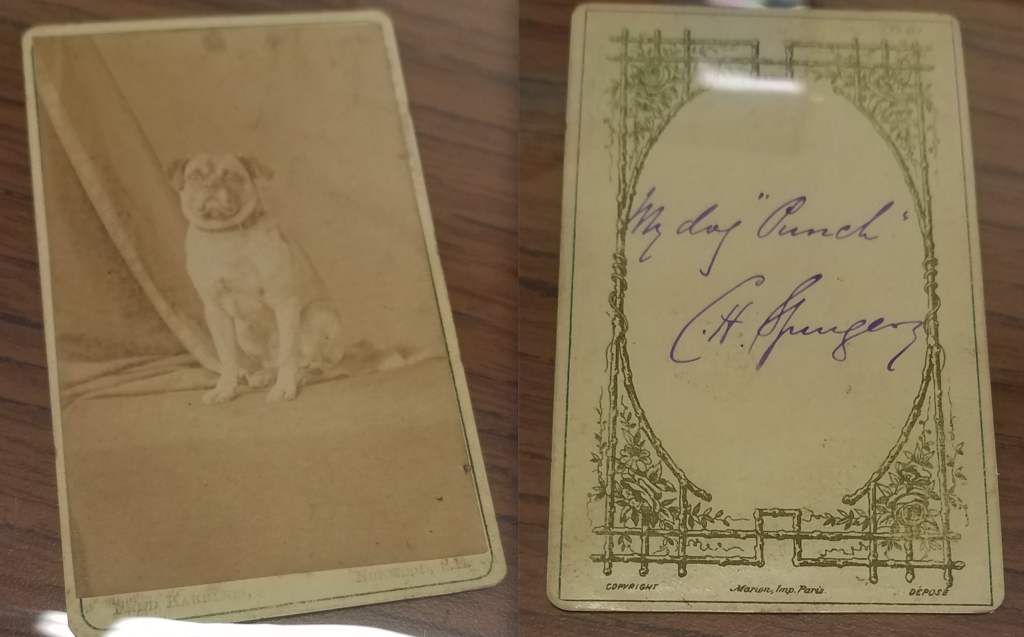

Like his previous home, he continued to own domestic animals like dogs, cats, and birds. But now, with the larger property, they occasionally had geese in the pond, and Spurgeon even tried his hand at beekeeping.[24] As before, all these animals found their way into his sermons and lectures. Spurgeon’s growing personal library, now housed adequately in his larger study, reflected his broad interest in animals, containing many books on animals and their care.[25] As he grew older, it appears that Spurgeon grew fonder of his pets, especially his dog “Punch.”[26] On one occasion, Spurgeon wrote a letter from Mentone expressing how much he missed Punch and was concerned for him because he heard that he was sick.[27] As one who was often ill himself, Spurgeon expressed sympathy for and found comfort in his pets.

When one reads Spurgeon’s story, it’s clear his divine calling was not to the animal world but to humanity. His ministry involved preaching the gospel to lost men and women. Therefore, it was strategic for Spurgeon to pastor a church in the most populous city of the world in the heart of the British empire, polluted and crowded as it was. At the same time, Spurgeon was not a cosmopolitan city-dweller. Instead, as his love of animals reveals, he was, at heart, a man of the country who loved nature. Though he had been transplanted into the city, Spurgeon looked for ways to create separation from city life so he could find refreshment and encouragement. Far from a utilitarian view of the animal world, these creatures were Spurgeon’s companions, pointing him to their Creator.

This paper was presented at the Andrew Fuller Center Conference in May 2021. You can read the rest of the presentation here.

[1] Gordon, W. J. The Horse World of London. (London: Religious Tract Society, 1893) 102.

[2] Cornish, C. J. Life at the Zoo; Notes and Traditions of the Regent’s Park Gardens. (London: Seeley & Co., 1895), 215-216.

[3] Kathleen Kete, ed. A Cultural History of Animals in the Age of Empire. (Berg, New York: 2011), 95. This innovation would not happen until after Spurgeon’s death. As a result, he found zoos oppressive for the animals. “Each of these creatures looks most beautiful at home. Go into the Zoological Gardens, and see the poor animals there under artificial conditions, and you can little guess what they are at home. A lion in a cage is a very different creature from a lion in the wilderness. The stork looks wretched in his wire pen, and you would hardly know him as the same creature if you saw him on the housetops or on the fir trees. Each creature looks best in its own place.” MTP 17:450

[4] Malcolm Smith, “A Hatful of Horror: the Victorian Headwear Craze that Led to Mass Slaughter,” https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/victorian-hats-birds-feathered-hat-fashion/

[5] One example of this cruelty is the treatment of pit ponies, who worked underground all their lives. “I’ve known ponies go all day without a bite or a drink. And working in hot places you know. They used to come into the stables after coal-turning [on the] morning shift. They would have half-an hour’s walk, be put into the stables for a drink and a bit of corn, then out again on the afternoon shift.” http://miningheritage.co.uk/pit-pony/ Web. April 29, 2021.

[6] “There is a certain class of exquisitely painful experiments to which these noble and intelligent animals seem particularly exposed.” These included both “the prolonged tortures of the veterinary schools… where sixty operations, lasting ten hours, were habitually performed on the same animal” and “some strictly physiological experiments upon horses and asses… [without] the use of any anesthetic whatever.” Statement of the Society for the Protection of Animals Liable to Vivisection. (Report of the Royal Commission on Vivisection. Westminster, 1876), 80-81.

[7] Darwin, Charles. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. (New York: Appleton & Co., 1871), 34.

[8] Sewell, Anna. Black Beauty: His Grooms and Companions. The Autobiography of a Horse. (London: Jarrold, 1877).

[9] For more on the history of the Battersea Dogs’ and Cats’ Home, see Jenkins, Garry. A Home of Their Own: The Heartwarming 150-year History of Battersea Dogs’ and Cats’ Home. London: Bantam, 2011.

[10] Christian George, The Lost Sermons of C. H. Spurgeon: His Earliest Outlines and Sermons Between 1851 and 1854, Vol. 1 (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2016), 10-21.

[11] C. H. Spurgeon, The Art of Illustration: Being Addresses Delivered to the Students of the Pastors’ College, Metropolitan Tabernacle (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1894), 63.

[12] Autobiography 1:20.

[13] Autobiography 1:14.

[14] George, Lost Sermons, xxxvi.

[15] Other sources that Spurgeon cites are “Penny Cyclopedia,” “Penny Magazine,” and “Print by S.P.C.K.”

[16] Autobiography 1:315.

[17] Autobiography 3:138. When the sale of Spurgeon’s sermons declined in the American South due to his outspoken condemnation of slavery, he considered selling his carriage to continue funding the Pastors’ College, but his deacons and elders refused to allow him to do so. For a humorous account of Spurgeon once cutting off a friend in traffic, see “The Mission to Scavengers,” The London City Magazine, No. 1002, Vol. 85, September 1920, 104.

[18] Autobiography 2:284.

[19] Autobiography 2:286.

[20] “We do not allow a gun in our garden, feeling that we can afford to pay a few cherries for a great deal of music, and we now have quite a lordly party of thrushes, blackbirds, and starlings upon the lawn, with a parliament of sparrows, chaffinches, robins, and other minor prophets. Our summer-house is occupied by a pair of bluemartens, which chase our big cat out of the garden by dashing swiftly across his head one after the other, till he is utterly bewildered, and makes a bolt of it. In the winter the balcony of our study is sacred to a gathering of all the tribes; they have heard that there is corn in Egypt, and therefore they hasten to partake of it and keep their souls alive in famine. On summer evenings the queen of our little kingdom spreads a banquet in our great green saloon which the vulgar call a lawn; it is opposite the parlor window, and her guests punctually arrive and cheerfully partake, while their hostess rejoices to gaze upon them.” S&T 1873:244-245.

[21] MTP 24:288.

[22] Gustavus D. Pike, The Singing Campaign for Ten Thousand Pounds; or, The Jubilee Singers in Great Britain (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1874), 86.

[23] Autobiography 4:57.

[24] Autobiography 4:59-60.

[25] In the Spurgeon Library in Kansas City, MO, there are nearly 40 volumes on the topic of animals that once belonged to Spurgeon. See Appendix 1.

[26] A photocard of Punch can be found in the Metropolitan Tabernacle archives in London.

[27] “I wonder whether Punchie thinks of his master. When we drove from the station here, a certain doggie barked at the horses in true Punchistic style, and reminded me of my old friend Punchie sending me his love pleased me very much… Poor doggie, pat him for me, and give him a tit-bit for my sake… I dreamed of old Punch; I hope the poor dog is better… Kind memories to all, including Punch. How is he getting on? I rejoice that his life is prolonged, and hope he will live till my return. May his afflictions be a blessing to him in the sweetening of his temper!… Tell Punchie, `Master is coming!” Autobiography 4:61.