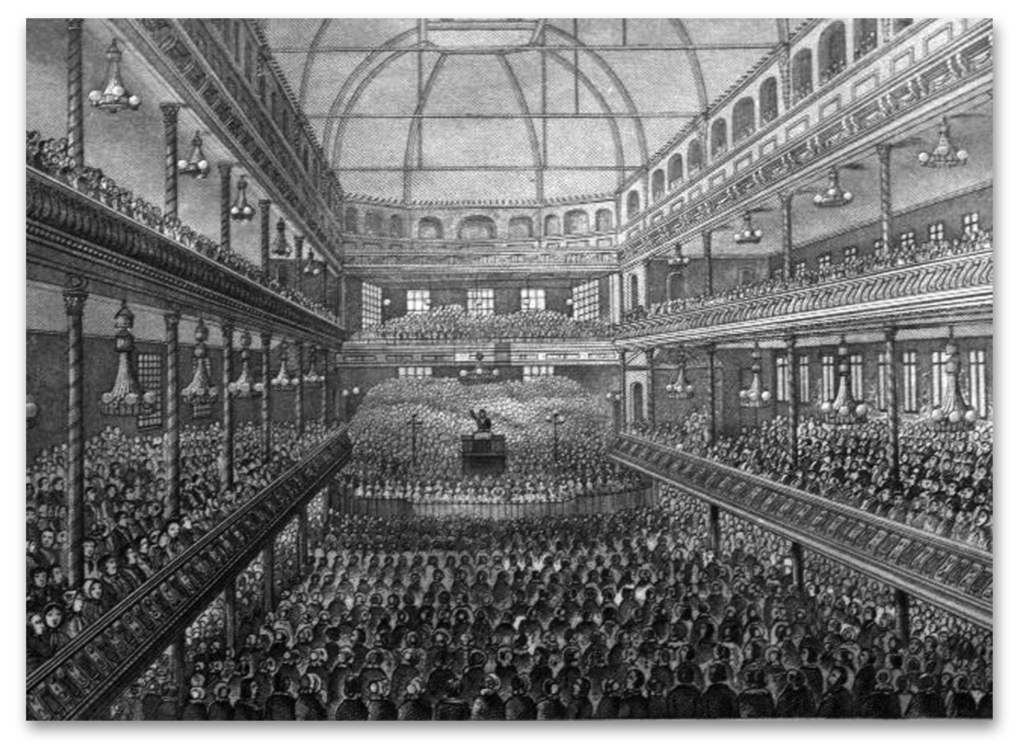

In the 19th century, Charles Spurgeon pastored the largest church in evangelicalism, reaching a membership of over 5,000 towards the end of his ministry. But despite its size, the Metropolitan Tabernacle operated fundamentally like any historic Baptist church. They built an ample meeting space to gather all together weekly for worship and prayer. Spurgeon preached 45-minute sermons. The congregation sang hymns acapella. They held congregational meetings. They maintained a rigorous membership process. They practiced church discipline. By all appearances, Spurgeon’s approach to pastoral ministry was not in itself all that unique. What was notable is that he did it with such a large church.

Of course, the church wasn’t always that large. When he began pastoring in London, the congregation was only a few dozen people. Spurgeon was a solo pastor working alongside five deacons. But the church multiplied under his preaching, reaching a membership of over 1,000 in just five years. This meant that Spurgeon had to adapt on the fly and adjust how he would care for so many people. The structures for a church of under a hundred were no longer sufficient now that it was over a thousand.

But in making those adjustments, Spurgeon never changed his core pastoral convictions. Spurgeon believed in the primacy of preaching and the proper administration of the ordinances. He held to regenerate church membership. He was a firm believer in congregational polity. And he believed in the pastor’s responsibility to shepherd Christ’s flock. Even with so many joining, Spurgeon refused to compromise his convictions about what the church or the pastor is to be.

In many ways, this dynamic of holding fast to convictions while being flexible to adjust to changing circumstances is like a dance. Just as a dance has a basic framework or structure, the pastor needs firm convictions about what the church should be and do. But within that structure, dancers have a lot of room for creativity and adaptation. Likewise, pastors need to be flexible as the needs and circumstances of their congregation change. Pastoring is not a mechanical process of following ten steps to success or the latest formula for growth. Pastoring is an art.

What did this look like for Spurgeon? How did he go about the art of pastoring?

Worship Gatherings

As an heir of the Reformed tradition, Spurgeon believed that Christ alone reigns over the church through his Word. This truth is to be seen supremely in the church’s worship. While Christians worship God in all of life, when it comes to the corporate gathering of the church, God has revealed how He is to be worshiped. This is what theologians call the Regulative Principle. Like the English Puritans before him, Spurgeon believed that the elements of a church’s worship gathering should only contain what God commands in Scripture. For Spurgeon, this included prayer, congregational singing, Scripture reading, preaching, and the ordinances of baptism and the Lord’s Supper.

As a result, the services at the Metropolitan Tabernacle were marked by simplicity. While other churches of the day experimented with new forms of entertainments, instruments, styles of preaching, and liturgies from other traditions, the worship at the Tabernacle remained the same throughout Spurgeon’s ministry. In fact, it wasn’t all that different from the church’s worship from its earliest days. As one deacon stated, “the services of religion have been conducted without any peculiarity of innovation. No musical or aesthetic accompaniments have ever been used. The weapons of our warfare are not carnal, but they are mighty.”[1]

But despite its simplicity, the worship at the Tabernacle was not stale or predictable. While the elements of Spurgeon’s liturgy were fixed, he had no problems varying the order of service, from the content of his extemporaneous prayers to the number of hymns, the length of Scripture readings, and more. As Spurgeon planned each service, he allowed the sermon text to guide the themes and emphases of each service. Speaking to his students, he advised them, “vary the order of service as much as possible. Whatever the free Spirit moves us to do, that let us do at once.”[2] Rather than letting the Regulative Principle become a straight-jacket, Spurgeon urged his students to remain sensitive to the leading of the Spirit.

In many ways, Spurgeon modeled this dynamic in his preaching. Throughout his ministry, Spurgeon was committed to preaching expositional sermons based on Scripture. “Let us be mighty in expounding the Scriptures. I am sure that no preaching will last so long, or build up a church so well, as the expository.”[3] While Spurgeon did allow for topical sermons and other kinds of sermons, he believed that the main diet of a church’s preaching should be expository sermons. As a result, the vast majority of Spurgeon’s 3,563 published sermons are an exposition and application of a Scriptural text.

However, Spurgeon refused to work mechanically through books of the Bible. Instead, every week, the most challenging part of his sermon preparation was prayerfully searching and waiting for the Spirit to lead him to the text that his people need to hear. In other words, Spurgeon believed every sermon he preached to be freshly given to him by God. The result of such a practice is nearly 40 years’ worth of sermons that are remarkable in their originality and diversity of application, illustration, and theological insight. Spurgeon’s sermons adapted to the challenges and circumstances that his congregation faced.

Prayer Meetings

In addition to the Sunday gatherings, Spurgeon was also committed to having a weekly congregational prayer meeting. Each Monday night, thousands would turn out to pray together for the ministry. Spurgeon believed that prayer was the engine that fueled the work of the church and taught his people to prioritize these meetings.[4]

But prayer meetings were not only necessary; Spurgeon also sought to make them lively. To maintain freshness, he regularly varied the themes of each meeting. By default, the church regularly prayed for the needs of church members, the preaching of the Word, and the salvation of the lost. But throughout the year, the church also devoted meetings for praying for the various ministries of the church – the Orphanage, the Pastors’ College, the many evangelistic and benevolent ministries of the church. When a church was planted, prayer meetings would be devoted to those endeavors. Once a month, the meeting was devoted to praying entirely for missions, and the church often heard from visiting missionaries like Hudson Taylor or Johann Oncken. At times, Spurgeon ordered the meeting around different theological themes.

All of this produced a weekly prayer meeting that was world-renowned. As famous as Spurgeon was for his preaching, those who visited the Tabernacle were often more encouraged by the Monday night prayer meeting than the Sunday services. Visitors from all over the world “carried away with them even to distant lands influences and impulses which they never wished to lose or to forget.”[5]

Church Membership

As a Baptist, Spurgeon believed the church was to be distinct from the world. And this distinction was to be expressed not through foreign customs or isolated communes but the practice of church membership. The church was to be made up of those who had a credible profession of faith, giving evidence to their new birth. Baptism, then, was the entrance into membership and the Lord’s Supper was the ongoing expression of membership in the church. Whereas many Baptists in his day watered down church membership and disconnected the ordinances from the discipline of the church, Spurgeon held these ecclesiological convictions firmly.

In his 38 years of ministry, Spurgeon brought over 14,000 people through the membership process at the Tabernacle. Each applicant was interviewed by an elder, met with the pastor, was visited by a church messenger, and voted on by the congregation. Everyone who was baptized at the Tabernacle was brought into church membership. And even as visitors flooded into the church, Spurgeon fenced the Table and required all participants to either be a member of the church or to interview with an elder first.

At the same time, though the membership process was rigorous, it was never meant to be daunting. Preaching on church membership, Spurgeon warmly declared,

Whenever I hear of candidates being alarmed at coming before our elders, or seeing the pastor, or making confession of faith before the church, I wish I could say to them: “Dismiss your fears, beloved ones; we shall be glad to see you, and you will find your intercourse with us a pleasure rather than a trial.” So far from wishing to repel you, if you really do love the Savior, we shall be glad enough to welcome you.[6]

In interviewing candidates, Spurgeon examined their understanding of the gospel, but he also took into consideration their background and age. His firm convictions regarding regenerate church membership did not make him insensitive to the pastoral needs of each applicant. Youth joining the church had to go through the same process as everyone else, but the elders did not expect from them the maturity of an adult. Those without an education might explain the gospel in a folksy way, but Spurgeon did not require an advanced vocabulary but a credible profession of faith. If any were unable to articulate the gospel, they were not condemned, but arrangements were made to meet with a church member to study the Bible. While Spurgeon held to regenerate church membership, this conviction created opportunities for him to shepherd even in the membership process.

Pastoral Care

Beyond bringing people in, Spurgeon believed that the membership rolls should mean something. In many churches, the membership rolls had simply become a sentimental record of those who at one time belonged to the church. Sometimes, they contained members who hadn’t attended in decades, had moved away to Australia, or had died! But at the Tabernacle, Spurgeon strived to make the membership roll an accurate representation of those regularly partaking of the Lord’s Supper and walking in fellowship with the Lord and one another.

With this conviction about his pastoral responsibility, it is this area, perhaps, where Spurgeon needed to exercise the most creativity. As the church grew into the thousands, Spurgeon adjusted by teaching on the biblical office of elders and leading his church to appoint elders for the spiritual care of the church. Apart from the tireless labors of his elders, he believed that the church would have been a sham. Spurgeon also divided the congregation into districts and assigned elders to oversee the different districts. This division of labor allowed the elders to shepherd the congregation meaningfully and not be overwhelmed by the task.

Members were also given communion tickets that helped track their attendance at the Table. If any member did not attend the Lord’s Supper for three consecutive months, the church clerk would notify the elders, and they would follow up. But non-attendance did not mean immediate removal. Instead, the elders saw this as an opportunity for pastoral care. Often, the non-attendance reflected financial, physical, or spiritual difficulties, and they stepped in to care for these members. The elders strived to exercise patience and wisdom in all these cases. Sometimes, non-attendance was the result of serious, unrepentant sin. In such cases, church discipline would need to be pursued, a matter that once again required great wisdom and care.

Conclusion

Today, many pastors struggle with holding on to biblical convictions in their ministry. Some pastors have a clear understanding of the gospel but have never been equipped with second-order doctrines of the church. As a result, they find themselves blown about by every wind of doctrine when it comes to the church and pastoral ministry. They have forgotten the framework of the pastoral dance, and as a result, their movements are erratic. Other pastors have clear convictions about pastoral ministry. But within that framework, they exercise their ministry mechanically, with little creativity or dependence on the Spirit.

Spurgeon reminds us that pastoral ministry is an art. Pastors must hold fast to their biblical convictions while demonstrating flexibility, patience, and creativity as they seek to implement those convictions amid their unique settings. Spurgeon’s example does not give us a blueprint for how to pastor. You are not Spurgeon, and your church is not the Metropolitan Tabernacle. As Peter instructed, our task is “to shepherd the flock of God that is among you” (1 Pet. 5:2). Even as we’re challenged and helped by his example, our task is to know our own people and to learn the art of pastoring, as we depend on God through His Word and in prayer.

[1] NPSP 5:350.

[2] Lectures 1:68.

[3] AARM 44

[4] S&T 1881:91.

[5] Autobiography 4:81.

[6] MTP 17:198-199.