Anyone engaged in pastoral ministry will need to grapple with feelings of personal hurt at some point or another. Occasionally these feelings are the fruit of misunderstanding, sin, or leadership failure on the part of the pastor. But other times, they arise from a genuine sense of abandonment or betrayal.

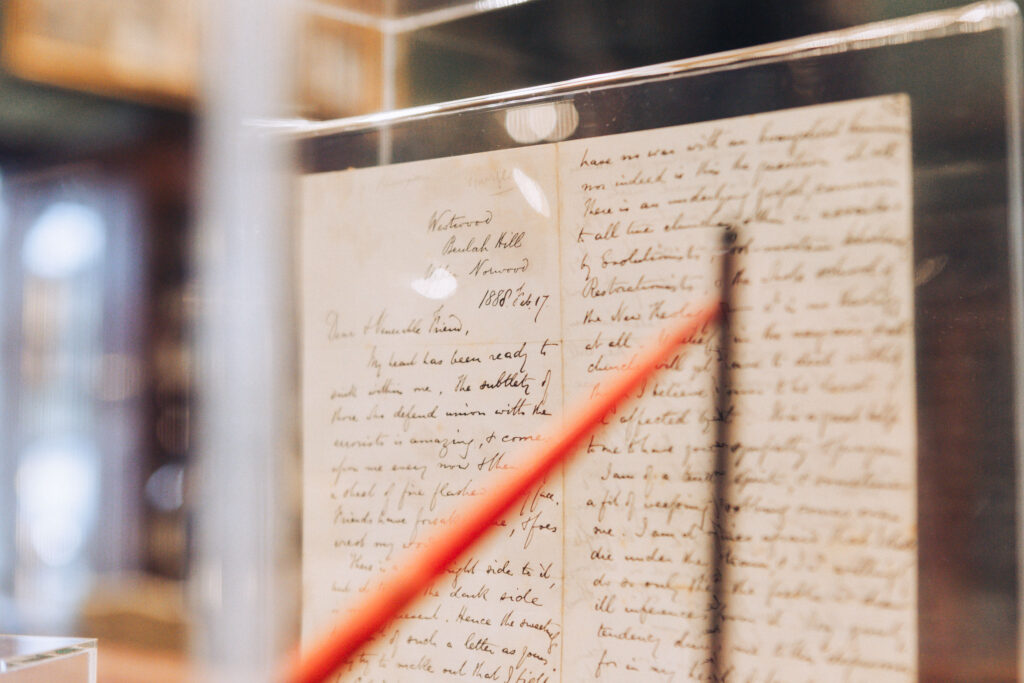

Spurgeon knew well the hurt that can accompany the departure of close friends. The latter portion of his ministry seemed acutely marked by convictional stands that brought with them a deep personal cost. But would Spurgeon’s later reactions to personal abandonment mirror his earlier writings on the topic? Would he, in short, practice what he preached? The record seems to indicate so.

Spurgeon and the Bible on Personal Hurt

Psalm 55 represents a touchstone passage on the visceral nature of relational breakdown. In it, David lamented over his broken relationship, likely with Saul or Ahithophel.[1] Indeed, David’s hurt is magnified not merely by the devices of his enemy, but by the close personal connection previously shared between them.

For it is not an enemy who taunts me—then I could bear it; it is not an adversary who deals insolently with me— then I could hide from him. But it is you, a man, my equal, my companion, my familiar friend. We used to take sweet counsel together; within God’s house we walked in the throng.

Psalm 55:12-14

Spurgeon treated this Psalm in his first volume of The Treasury of David. This work was likely finalized in late 1869 and was being sold from bookstore shelves by November 1870.[2] In it, Spurgeon taught the following:

None are such real enemies as false friends. Reproaches from those who have been intimate with us, and trusted by us, cut us to the quick; and they are usually so well acquainted with our peculiar weaknesses that they know how to couch us where we are the most sensitive, and to speak so as to do us the most damage. The slanders of an avowed antagonist are seldom so mean and dastardly as those of a traitor, and the absence of the elements of ingratitude and treachery renders them less hard to bear. . . We can find a hiding-place from open foes, but who can escape from treachery?[3]

Spurgeon waxed poetic on the deep hurt of betrayal:

“But thou.” Et tu, Brute? And thou, Ahithophel, art thou here? Judas, betrayest thou the Son of Man? “A man mine equal.” Treated by me as one of my own rank, never looked upon as an inferior, but as a trusted friend. . . Religion had rendered their intercourse sacred, they had mingled their worship, and communed on heavenly themes. If ever any bonds ought to be held inviolable, religious connection should be.[4]

It is true that the closer the relationship, the greater the propensity for hurt when a relationship breaks down. David knew this from experiencing outright betrayal. Spurgeon knew it from experiencing the departure of those he’d mentored during a time of doctrinal upheaval.

One of My Own Rank

As far back as two decades before the Down Grade Controversy got fully underway, Spurgeon was engaged in a debate with the Baptist Missionary Society over who could be a member and to what degree the society would be unabashedly evangelical. Spurgeon had a vested interest in these questions since he was a prominent member and some of his own Pastor’s College graduates had served under the BMS’s auspices.[5]

After a season of sustained advocacy for orthodoxy and prudent organizational parameters among these affiliations, Spurgeon decided to withdraw. By October 1887, Spurgeon withdrew from the Baptist Union. In November 1887, Spurgeon announced his rationale for withdrawal from the BU.[6] In April 1888, he withdrew from the London Baptist Association, which he had helped to found. He desired to go quietly, seeing no fruit in continued advocacy within these organizations. In truth, the process hurt him deeply. The Baptist Union Council charged him of making ill-founded accusations of doctrinal infidelity and censured him.[7] The resolution to censure was moved by William Landels, an erstwhile stalwart companion during Spurgeon’s Baptismal Regeneration Controversy. To make matters worse, Spurgeon’s own brother, James, believing himself to be helping Charles’s cause, advocated for the adoption of a would-be conciliatory statement seeking to appear more in line with Spurgeon’s view. The statement was adopted, but for Charles, he wasn’t sufficiently vindicated from the false accusations.[8] The damage was done, and the Council wasn’t relenting. He lamented,

My brother thinks he has gained a great victory, but I believe we are hopelessly sold. I feel heartbroken. Certainly he has done the very opposite of what I should have done. Yet he is not to be blamed, for he followed his best judgment.[9]

While the distancing from Spurgeon of such figures as Landels and the disappointment brokered by his brother proved palpable, Spurgeon was only entering the storm. After he felt it necessary to reorganize his Pastor’s College under clearly evangelical auspices, adopting a statement of faith very similar to the proposal rejected by the Baptist Union, some 80 students revolted. They refused to follow Spurgeon into his re-tooled College. This proved devastating to Spurgeon. He penned to one friend,

“I cannot tell you by letter what I Have endured in the desertion of my own men. Ah me! Yet the Lord liveth, and blessed be my rock!”[10]

Spurgeon’s Prescription Considered

In commenting on how one might be sustained during times of abandonment and betrayal, Spurgeon provided a few prescriptions.

First, he encouraged looking to the example of Christ, who too “had to endure at its worse the deceit and faithlessness of a favored disciple.” He continued,

“let us not marvel when we are called to tread the road which is marked by his pierced feet.”[11]

Second, he counseled calling upon God alone as a source of solace.

“As for me, I will call upon God.” The Psalmist would not endeavor to meet the plots of his adversaries by counterplots, nor imitate their incessant violence, but in direct opposition to their godless behaviour would continually resort to his God.[12]

He pointed to the victory to be had in the privacy of the prayer closet:

Some cry aloud who never say a word. It is the bell of the heart that rings loudest in heaven.[13]

Finally, he entrusted himself to the vindication of God, believing that even God’s stripping us of friends is a vehicle of his kind, sanctifying power.

The Lord can soon change our condition, and he often does so when our prayers become fervent. The crisis of life is usually the secret place of wrestling. . . He who is stripped us of all friends to make us see himself in their absence, can give them back again in greater numbers that we may see him more joyfully in the fact of their presence.[14]

Physician, Heal Thyself

The exhortations written years before Spurgeon’s controversy convey one level of credence when surveyed in isolation. But when considered in light of Spurgeon’s practicing of his own remedies, they prove all the more meaningful.

Where Spurgeon could speak, he spoke. He advocated for truth in the institutions where he had a platform. But when that influence proved ineffectual, he withdrew, preferring not to “meet plots with counterplots,” and instead entrusting himself and his cause to the Lord in quiet submission.

Yet at his Pastor’s College, a realm more squarely under his purview, Spurgeon effected reform, and at great cost. When his mentees departed by the score, he rehearsed a refrain similar to the one penned from Psalm 55: “Yet the Lord liveth, and blessed be my rock!”

Spurgeon wrote powerfully of the personal hurt David endured when seeking to be faithful to the Lord. Little did he know that he too would be called upon to live out his own creed. Readers today do well to follow Spurgeon’s pattern in this regard: contending for the truth, yes, but looking to the Lord for final vindication.

[1] Spurgeon took the betraying friend of Psalm 55 to be Ahithophel. Charles H. Spurgeon, “Psalm LV,” in The Treasury of David, vol. 1 (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1988), 447-48. While Calvin took David’s enemy here to be Saul, other scholarship agrees with Spurgeon on this point. Cf. John Calvin Commentary on the Book of Psalms, vol. 2, trans. James Anderson (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2010), 327; Carl Friedrich Keil and Franz Delitzsch, Commentary on the Old Testament, vol. 5 (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1996), 381.

[2] Spurgeon notified his The Sword and the Trowel readers of the impending project release in November 1869. Charles Haddon Spurgeon, The Sword and the Trowel, November 1869, p.524. See also Thomas J. Nettles, Living by Revealed Truth: The Life and Pastoral Theology of Charles Haddon Spurgeon (Fearn, UK: Mentor, 2013), 400-401.

[3] Spurgeon, “Psalm LV,” in Treasury of David, vol. 1, 448.

[4] Ibid., 449.

[5] Larry James Michael, “The Effects of Controversy on the Evangelistic Ministry of C. H. Spurgeon” (PhD diss., The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989), 194.

[6] Spurgeon, “A Fragment Upon the Down-Grade Controversy,” Sword and Trowel, November 1887, 558.

[7] Ernest A. Payne, The Baptist Union: A Short History (London, UK: The Carey Kingsgate Press Ltd., 1958), 136.

[8] It should be noted that at some points, scholars leave open the question of whether the objective actions of others or the subjective interpretation of Spurgeon caused his feelings of abandonment. These questions notwithstanding, the history of the Baptist Union’s trajectory largely vindicates Spurgeon in his feeling that men with whom he had once held fast to sound doctrine were drifting.

[9] W. Y. Fullerton, Charles H. Spurgeon: London’s Most Popular Preacher (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1966), 256.

[10] Miscellaneous correspondence, Spurgeon’s College, London. Quoted in Michael, 251.

[11] Spurgeon, “Psalm LV,” in Treasury of David, vol. 1, 449.

[12] Ibid., 450.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.