One of the Apostle Paul’s assumptions for pastors is that the man of God would be a man of learning. His pastoral calling would, in fact, also be a calling to deep, ambitious study. To handle rightly the word of God and to divide truth from error requires that the elder learn.

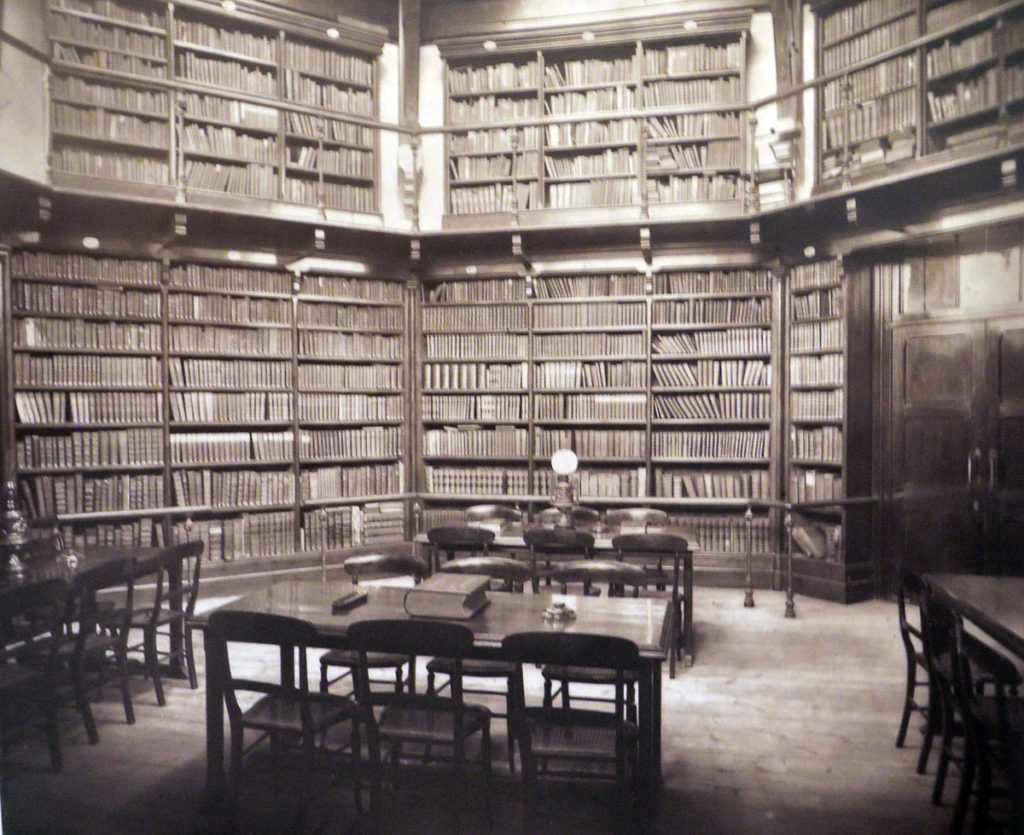

For centuries, this kind of learning meant that pastors would be men of books—yes, men of the Book, but also men of other books as well. The pastor would be one whose library was well stocked with everything needed to guard the faith and encourage godliness. After the invention of the printing press, ordinary pastors in Western Europe could acquire a library of several hundred books with relative ease. C. H. Spurgeon was one such minister who built a pastoral library of over 12,000 volumes with the ultimate goal of presenting a more-pure bride to Christ.

C. H. Spurgeon was no ordinary pastor, and neither was his pastoral library. My doctoral research focused on Dutch ministers and their pastoral libraries, and it is clear that his library was orders of magnitude larger than any Dutch minister from the seventeenth century. The average size of a Dutch minister’s library that sold at an auction was 1,138 books. The closest is that of Balthazar Lydius, and he owned just under six thousand books.

Building a pastoral library, Spurgeon thought, should be part and parcel of the work ministry. He even encouraged deacons to find funds to help their pastors build their libraries. He wrote, “A good library should be looked upon as an indispensable part of church furniture; and the deacons, whose business it is ‘to serve tables,’ will be wise if, without neglecting the table of the Lord, or of the poor, and without diminishing the supplies of the minister’s dinner-table, they give an eye to his study-table.”

Spurgeon was also a realist. He recognized that not every minister had the financial capability to acquire several thousand books. For pastors who had fewer books, he provided two pieces of advice: 1. Buy a few, high-quality books; 2. “Master those books you have.” “Read them thoroughly,” he wrote. “Bathe in them until they saturate you. Read and re-read them, masticate them, and digest them. Let them go into your very self. Peruse a good book several times, and make notes and analyses of it. A student will find that his mental constitution is more affected by one book thoroughly mastered than by twenty books which he has merely skimmed, lapping at them, as the classic proverb puts it ‘As the dogs drink of Nilus.’”

Part of my research was analyzing the contents of 17th-century Dutch ministers’ libraries. Unfortunately, records of most pastoral libraries were either never written or the records are now lost. But there are a few exceptions to that. For a Dutch minister in the seventeenth century, if his library was large enough, his widow would on occasion have a book-seller draw up a list of all the books she wanted to auction after his death, and the list would be distributed to other book-sellers to inform potential buyers of the impending auction. In my doctoral research, I have found 236 of these auction catalogs that survive from Dutch ministers’ libraries. (Several hundred other auction catalogs from this era survive for ministers in other Western European countries).

In Spurgeon’s case, however, much of his library is preserved in the Spurgeon Library in Kansas City, MO, and the Library has a catalog of all the books in their collection, over 6,000 volumes. What pastoral wisdom might a pastor glean from Spurgeon’s library?

Every pastor’s library I have come across, including Spurgeon’s, has timeless and timely theological works. The ideal library for a minister was one with a core of certain types of books upon which all ministers had to build (Calvin, Augustine, Luther, etc.) and the printed relics of controversies from their particular era grounding the library in a specific time and place. Spurgeon had both of these in spades. Spurgeon’s library is built on these twin-pillars: books whose theological value has endured for generations and those books whose writing was occasional—they were significant in a particular moment.

Spurgeon, like Dutch ministers before him, also read books that would have been of great importance to his congregation. He wasn’t just a theologian—he was a public intellectual who sought to show his congregation how all of life was to be lived as unto God. In order to do that faithfully, Spurgeon acquired books on medicine, different vocations (mining for instance), and many others. He sought to understand the daily life of his people so that in his pastoral work, he could address specific pastoral needs that might arise.

From just a cursory glance at his library, it seems clear that Spurgeon read books of national and political interest. He had a real interest in the lands Britain was engaged in at the time. There are many books on their colonies, including at least one book of proverbs from India. There is a real possibility that he had these, in part, because he found them interesting. He owned many works of fiction and he also owned a particularly interesting book on Yellowstone National Park. Reading was clearly something he did for leisure in addition to his study. But why these books on nations who were under British rule? Spurgeon considered it his pastoral calling to understand the cultural conversations of the day, and enrapturing news from these far-flung places would have been part of everyday discussions. So in order to serve his congregation, Spurgeon may have considered it well worth the time and effort to acquire and read these books.

Robust thinking is part and parcel of the faithful minister’s calling. That demands that we read books. A library is a tool in pastoral ministry that ought to be used intentionally. Spurgeon used the ubiquitous analogy that books “provide food for the minister’s brain.” He celebrated the idea that churches would band together to provide their ministers with enough income so that they could feast on a steady diet of good, soul-enriching books.

And yet for all that, the one thing that ought not to be forgotten, Spurgeon warned, is that the celestial food of Scripture ought to be our all-encompassing delight. “Visit many good books, but live in the Bible.”

Forrest C. Strickland (Ph.D., University of St Andrews) serves as Adjunct Instructor of History at Liberty University and Adjunct Professor of Church History at Boyce College.