Someone somewhere has said, “some things are better caught than taught.” Many would argue that this is true with preaching. It is one thing to learn about preaching in the abstract from books or classroom lectures. It is something else entirely to learn from the example of faithful preachers.

C. H. Spurgeon possessed a remarkable preaching genius that was as original as it was extraordinary. He began preaching at the age of sixteen without the benefit of any formal training, and within just a few years he secured one of London’s most prestigious nonconformist pulpits. There he would preach in the heart of London to thousands upon thousands for nearly four decades. Romantics would say he was born a preacher. Secular historians would say he was the product of external social and cultural forces that coalesced to make him what he was. Of course, believers in the power of the Holy Spirit would say that Spurgeon experienced an unusual anointing from God. The Puritans who Spurgeon so admired liked to call this anointing “unction.” Whatever one may call it, Spurgeon had it, and he had it before he was even old enough to shave.[1]

Though Spurgeon was something of a preaching prodigy who probably would have fared just fine without any teachers, he nonetheless “caught” good preaching from a number of important exemplars. He certainly learned a great deal about preaching from his father and grandfather; the former, an itinerant lay-preacher, and the latter, a nonconformist minister who preached regularly for over fifty years. Spurgeon also benefitted considerably from studying the ministries of George Whitefield and John Wesley.[2] Spurgeon identified Whitefield in particular as his model.[3]

A lesser known influence on Spurgeon was Charles Simeon (1759-1836), who Spurgeon dubbed “The famous English clergyman of Cambridge.”[4] In 1850, Spurgeon moved to Cambridge where Simeon had commanded the pulpit of Holy Trinity Church for more than half a century. Simeon was a crucial early influence on Spurgeon in his beginning days as a preacher. Spurgeon preached his first sermons in connection with the Cambridge Lay-Preachers’ Association, and did most of his early preaching in and around Cambridgeshire where the legacy of Simeon was still alive and well fifteen years after his death.

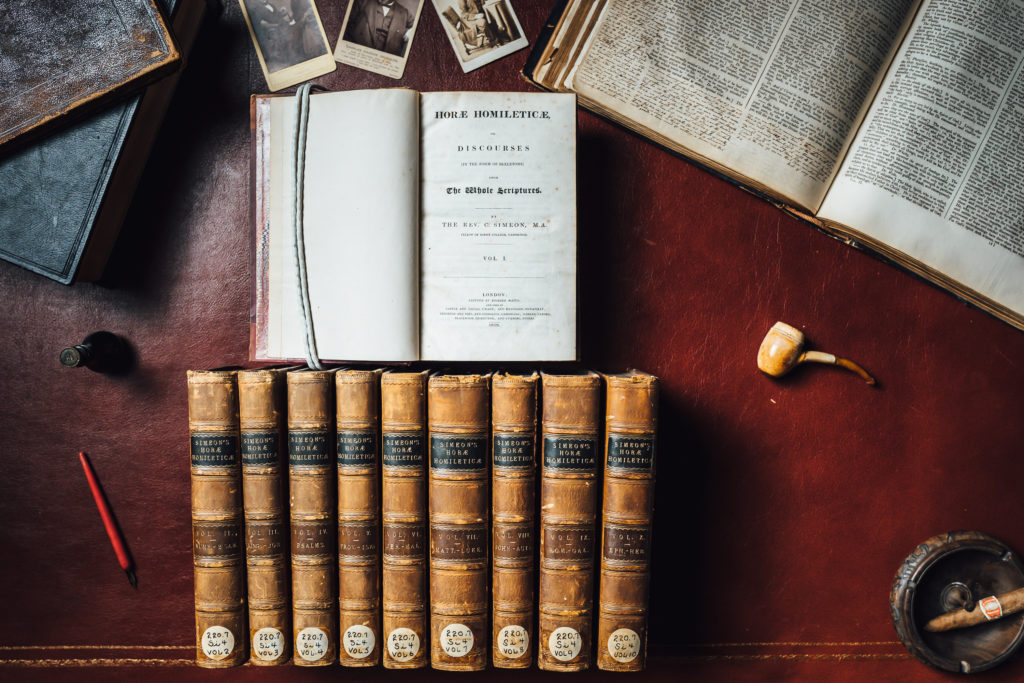

The primary means by which Spurgeon absorbed Simeon’s influence was through his massive multi-volume collection of skeleton outlines, titled Horae Homileticae.[5] In Spurgeon’s Commenting and Commentaries, he commends Simeon’s Horae Homileticae with this note: “Not commentaries, but we could not exclude them. They have been called ‘a valley of dry bones’: be a prophet and they will live.”[6]

The editors of the Lost Sermons of C. H. Spurgeon have identified Simeon’s significant influence on Spurgeon’s earliest sermon outlines.[7] Many of them borrow heavily from Simeon’s sermons, and some even use his words verbatim.[8] It is fascinating to imagine the sixteen year old Spurgeon pouring over Simeon’s sermon outlines in preparation to preach in a nearby village just outside of Cambridge.

But who was Charles Simeon and how did he emerge as a figure of such great influence?

Charles Simeon spent almost his entire adult life in Cambridge.[9] Though his ministry was centered in one place, he nonetheless left an indelible stamp on the wider evangelical world. As a preacher, Simeon published twenty-one volumes of sermon outlines covering the entire Bible. As a college dean, he mentored a host of future ministers and missionaries. As one of the elder statesmen of the evangelical movement in Britain, he participated in various societies, forwarded the cause of missions, and enjoyed seasons of fruitful itinerant ministry. Further, he engaged in close correspondence with other prominent evangelicals such as John Newton, William Wilberforce, Thomas Chalmers, and Henry Venn.

Without question, the central work of Simeon’s life was his preaching ministry. For more than fifty years he expounded the Bible Sunday by Sunday in the pulpit of the historic Holy Trinity Church. When Simeon arrived in Cambridge in the late 1770s, the evangelical movement had barely grazed the Church of England. By his death in 1836, it is estimated that a third of Anglican pulpits were evangelical.[10] Such a massive shift in the established church would have been unthinkable apart from the sustained influence of Charles Simeon. Through his preaching, God was pleased to revitalize a church, raise up a new generation of preachers, and galvanize a movement.

At the age of twenty-three, Simeon was appointed vicar of Holy Trinity, a church that enjoyed an extraordinary heritage of storied preachers such as Richard Sibbes and Thomas Goodwin. One might assume that the young Simeon was warmly received by his new congregation. This was not so. The circumstances of his appointment were controversial, resulting in the congregation’s bitter opposition toward Simeon for many years.[11] The parishioners deprecated Simeon’s evangelical convictions. Their dislike of their new vicar was such that they made every effort to impede his ability to preach. Regularly, the churchwardens would lock the building to prevent the hearing of Simeon’s sermons. Members of the church not only boycotted his preaching, but some of them even went as far as to lock their pews in the church to prevent others from going to hear the young minister.[12] Such ignoble antics were the norm for Simeon for the first several years of his ministry. Even when some of these more extreme measures subsided, many of his parishioners remained cold toward him and the gospel he preached. In such seasons, Simeon found comfort in Paul’s words to Timothy, “the Lord’s servant must not be quarrelsome but kind to everyone, able to teach, patiently enduring evil.” Though bruised by the opposition of his flock, Simeon emerged through these trials with a warmhearted commitment to the spiritual good of his congregation.

As a Fellow of King’s College, and later the Dean, Simeon made a steady habit of mentoring young men. These relationships were not primarily academic, but spiritual in nature. Simeon gave most of his time to men who aspired to ministerial service. The most famous of these men was Henry Martyn, who served as Simeon’s curate, and later as a missionary to India.

Simeon made concerted efforts to mentor young men through various means. He hosted regular tea meetings for anyone interested in asking questions about the Bible.[13] These “conversation parties” normally took place on Friday nights with up to eighty students crammed into a sitting room. There they probed the mind of the veteran preacher regarding Scripture, theology, and pastoral ministry. At these meetings, Simeon made a point of personally acquainting himself with each of his guests. When a young man attended a conversation party for the first time, he seldom left without Simeon greeting him and recording his name in a journal.

Simeon also hosted sermon classes for men called to preach.[14] These smaller gatherings were by invite only. In each session, Simeon would offer a text for consideration. Men would then be charged to produce a sermon outline for the text. After presentations, feedback would follow. Thus, Simeon slowly transmitted his particular brand of evangelical preaching to an entire generation of Anglican ministers.

The pulpit of Holy Trinity was of course the primary means by which Simeon exerted his influence, and his preaching is what remains his most enduring legacy today. The twenty-one volumes of Horae Homileticae capture well Simeon’s method of expository preaching. These sermon skeletons have served preachers for generations, including a young Charles Spurgeon who read Simeon’s sermons as a teenager. Simeon was renowned for his regular verse by verse exposition of biblical texts. He said, “My endeavor is to bring out of Scripture what is there, and not to thrust in what I think might be there.”[15] According to Simeon, true preaching must ultimately possess three chief aims: to humble the sinner, exalt the savior, and promote holiness.[16] For over five decades, Simeon gave himself to this kind of preaching in the pulpit of Holy Trinity. Over the years, thousands came to hear Simeon preach, including hundreds of future ministers who embraced Simeon’s evangelical faith. Even some fifteen years after his death, budding preachers like Charles Spurgeon were still taking in Simeon’s influence.

It should humble aspiring preachers today to know that even someone as uniquely gifted as Spurgeon still sought out preaching models. If preaching is better caught than taught, Spurgeon wanted to catch it from the very best preachers he could find. In Simeon’s sermons, Spurgeon discovered something of a mentor in preaching. Simeon provided the young Spurgeon with a model for how to faithfully preach Christ, and to do so with earnestness, simplicity, and power. Surely Spurgeon would encourage preachers today to rediscover Simeon’s sermons. Though they may once again be considered by some to be a valley of dry bones, Spurgeon assures us, “be a prophet and they will live.”

Alex DiPrima is the senior pastor of Emmanuel Church in Winston Salem, NC. He holds a Ph.D. from SEBTS and wrote his dissertation on the social ministry of C. H. Spurgeon.

Zack DiPrima is a pastoral assistant at Emmanuel Church in Winston Salem, NC. He is currently working on his Ph.D. from SBTS and is studying the ministry of Charles Simeon.

[1] Spurgeon, Autobiography, 1:298.

[2] Spurgeon, Autobiography, 1:176. Spurgeon said, “[I]f there were wanted two apostles to be added to the number of the twelve, I do not believe that there could be found two men more fit to be so added than George Whitefield and John Wesley.’

[3] Spurgeon, Autobiography, 2:66; see also William Williams, Personal Reminiscences of Charles Haddon Spurgeon (London: Religious Tract Society, 1895), 180.

[4] Spurgeon, MTP, 30:179

[5] Charles Simeon, Horae Homileticae: or Discourses (Principally in the Form of Skeletons) Now First Digested Into One Continued Series, and Forming a Commentary Upon Every Book of The Old and New Testament, etc. (London: Holdsworth and Ball, 1832).

[6] Spurgeon, Commenting and Commentaries: Two Lectures Addressed to the Students of the Pastors’ College, Metropolitan Tabernacle, Together with a Catalogue of Biblical Commentaries and Expositions (London: Passmore and Alabaster, 1876), 42.

[7] Spurgeon, The Lost Sermons of C. H. Spurgeon: His Earliest Outlines and Sermons Between 1851 and 1854, Edited with Introduction and Notes by Christian George, Vol. 1 (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2016), 258.

[8] Spurgeon, The Lost Sermons, 295.

[9] The best available biographies on Charles Simeon are Hugh E. Hopkins, Charles Simeon of Cambridge (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1977); Handley C. G. Moule, Charles Simeon (London: Methuen & Co, 1892); and

Derek Prime, Charles Simeon: An Ordinary Pastor of Extraordinary Influence (Leominster, UK: Day One Publications, 2011).

[10] Derek Prime Charles Simeon: An Ordinary Pastor of Extraordinary Influence, 239

[11] William Carus, Memoirs of the life of the Rev. Charles Simeon, M.A., Late Senior Fellow of King’s College and Minister of Trinity Church, Cambridge (London: J. Hatchard & Son, 1847), 40–3.

[12] Carus, 43–5.

[13] Abner W. Brown, Recollections of the conversation parties of the Rev. Charles Simeon, M.A., Senior Fellow of King’s College, and Perpetual Curate of Trinity Church, Cambridge (London: Hamilton, Adams, & Co, 1863), 51–3.

[14] Brown, 51–3

[15] Moule, 97.

[16] Charles Simeon , Horae Homileticae Vol. I, (London: Holdsworth and Ball, 1832), xxi.