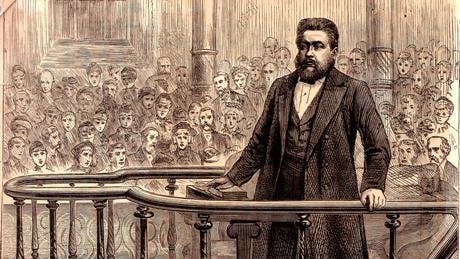

When Charles Spurgeon first arrived in London in the winter of 1853, the New Park Street Chapel had severely dwindled from its historic past. This congregation had once been pastored by men like Benjamin Keach, John Gill, and John Rippon, and had played a leading role among Baptists in Britain. But by 1853, they had seen several pastoral transitions in quick succession. Not only that, but the church had relocated to a problematic place that was hard to access. So, on that cold morning, when Spurgeon mounted the pulpit, there were barely a hundred in that cavernous room which seated twelve hundred.

Yet, that morning, the congregation heard a kind of preaching that they had never heard before:

But reminding you that there is no change in His power, justice, knowledge, oath, threatening, or decree, I will confine myself to the fact that His love to us knows no variation. How often it is called unchangeable, everlasting love! He loves me now as much as He did when first: He inscribed my name in His eternal book of election. He has not repented of His choice. He has not blotted out one of His chosen; there are no erasures in that book; all whose names are written in it are safe for ever. Nor does God love me less now than when He gave that grand proof of love, His Son, Jesus Christ, to die for me. Even now, He loves me with the same intensity as when He poured out the vials of justice on His darling to save rebel worms. [1]

Here was preaching that exalted the majesty of God, and yet was understandable; preaching that proclaimed the reality of sin, and yet held forth the beauty of the gospel. The members were thrilled with what they had heard. When the service ended, they hurriedly pressed the deacons to invite this young man back to preach. One of the deacons remarked that if they wanted this young man to return, they should go home and invite their neighbors to come, lest he be discouraged at their small size! And so, they did. By that evening, the attendance had doubled.

Commenting on this occasion many years later, Spurgeon remarked,

Somebody asked me how I got my congregation. I never got it at all. I did not think it my business to do so, but only to preach the gospel. Why, my congregation got my congregation. I had eighty, or scarcely a hundred, when I preached first. The next time I had two hundred — every one who had heard me was saying to his neighbor, “You must go and hear this young man.” Next meeting we had four hundred, and in six weeks eight hundred. That was the way in which my people got my congregation.[2]

And this would be true not only in those early days but throughout the rest of Spurgeon’s ministry. There is no doubt that Spurgeon was a gifted and faithful preacher. But this is only half of the story. His congregation was also faithful in reaching out to those around them. And this was particularly true when it came to visitors in attendance.

Sometimes, Spurgeon’s preaching would result in a radical conversion where the individual would be ready to meet with the pastor and join the church. But more often, visitors would be intrigued by the preaching and experience a measure of conviction, but have further questions, or doubts, or fears, or all kinds of other concerns that would keep them from meeting with the pastor or an elder. With hundreds of visitors that attended each week, there was no way that Spurgeon could meet with every single one of them. This is why he taught his congregation not merely to visit with one another after the service but to be ready to engage those around them.

One elder in particular modeled this. Spurgeon writes,

One brother has earned for himself the title of my hunting dog, for he is always ready to pick up the wounded bird. One Monday night, at the prayer-meeting, he was fitting near me on the platform; all at once I missed him, and presently I saw him right at the other end of the building. After the meeting, I asked him why he went off so suddenly, and he said that the gas just shone on the face of a woman in the congregation, and she looked so sad that he walked round, and sat near her, in readiness to speak to her about the Savior after the service.[3]

Here, Spurgeon envisions himself as a hunter. In his preaching, he is firing the truth of the gospel at sinners, and the result is that many are wounded, that is, that are under conviction. Now, it was up to his people to talk to those people, like hunting dogs picking up wounded birds.

This is what Spurgeon expected not only from his elders but also from the members of his church. The last thing Spurgeon wanted was for a visitor to sit through a service unnoticed and without being engaged. He writes, “Every believer should be doubly on the alert in watching for souls. None in that congregation should be able to say, ‘We attended that place, but no one spoke to us.’”[4] But this was not merely about greeting visitors and making them feel welcome. Spurgeon wanted his people to talk to visitors about the sermon and the gospel.

I always ask my own congregation to preach Christ in the pews. Get hold of the people who come there and tell them about Christ. I know people are a little starched up about the matter sometimes — a little mahogany comes between them and their fellows, but in the church there should be cordiality — the feeling that a man may venture to speak to his neighbor; to say, at least, “How did you enjoy the sermon?” to start the conversation, and detain him for a little while.[5]

Of course, not every visitor was interested in talking. The church had developed a reputation for engaging visitors, and sometimes people wanted their space. Yet, Spurgeon was willing to risk annoying their visitors if it meant that they were confronted with the gospel. This was the cost of attending the Metropolitan Tabernacle to hear Spurgeon preach.

I do not think any sermon ought to be preached without each one of you Christian people saying, ‘I wonder whether God has blessed the message to this stranger who has been sitting next to me. I will put a gentle question to him, and see if I can find out.’ I have known some hearers to be annoyed at such a question being put to them by an earnest brother. Do not be annoyed, dear friend, if you can help it, because you are very likely to be treated in that way again. It is our custom to do it here, so you will have to put up with it; and the only way to get over the annoyance is to give your heart to Christ, and settle the matter once for all.”[6]

Because of this evangelistic hospitality, over the course of 38 years of ministry, thousands were converted at the Metropolitan Tabernacle. However, this was due to the ministry of not just one man, but the entire church.

Today, pastors are right to labor in their evangelistic preaching. However, it’s also important to remember that this is only half of the picture. Pastors also need to give their people a vision for the role that God has called them to play on Sunday mornings. Even as pastors give themselves to preaching excellent sermons, they should also help their congregations feel the stewardship of the evangelistic opportunities around them. If you are a church member, are there visitors you can talk to after the service about the sermon? Is there a neighbor to whom you can give a sermon link? Or even during this time of the pandemic, could you invite a friend to join the live stream and then offer to have a socially-distanced lunch during the week? Just as pastors faithfully labor to preach the gospel, so should church members do all they can to take advantage of any gospel opportunities around them.

May Spurgeon’s praise for his congregation be true in our churches today also.

We owe very many of the conversions that have been wrought here to the personal exertions of our churchmembers. God owns our ministry, but he also owns yours. It is to our delight at church-meetings that when converts come they often have to say that the word preached from the pulpit was blessed to them, and yet I think that almost as often they say it was the word spoken in some of the classes, or in the pews; for not a few of you have been spiritual parents to strangers who have dropped in. Do this still.[7]

[1] Spurgeon, Autobiography, 1:325.

[2] Spurgeon, Speeches at Home and Abroad, 65-66.

[3] Autobiography 3:23.

[4] S&T 1872:441

[5] Spurgeon, Speeches at Home and Abroad, 65.

[6] MTP 46:438.

[7] MTP 58:429-430.