The year was 1855 as controversy brewed about the pews of London over the publication of a hymn-book entitled, The Rivulet. Penned by the local minister Thomas Lynch, the book raised more than a few ministerial eyebrows for its lack of explicit Christian orthodoxy. The hymn-book quickly acquired the epithets, “pantheistic,” “written by a Deist” with “not one particle of vital religion or evangelical piety.” The crux of the issue was not the quality of the poetry, but rather the absence of doctrinal clarity in the lyrics. As Charles Spurgeon cheekily put it, “Certainly, some verses are bad…but others of them, like noses of wax, will fit more than one face.”

Spurgeon’s main concern with The Rivulet was Lynch’s insistence that the hymnal be used in congregational worship. Spurgeon did not object to using the book in private, but to sing its hymns in the gathering of the saints was unthinkable. He said, “A book may be very excellent, and yet unfit for certain purposes.” In Spurgeon’s view, the book was so devoid of any useful doctrine that its lyrics could not “cheer us on a dying bed.” Though The Rivulet is filled with beautifully crafted lyrics, he claimed that “she who would wash the feet of the God-man, Christ Jesus, with her tears, will never find a companion in this book.” In other words, congregational singing should be centered on the saving work of Jesus.

But this was not a legalistic requirement. Rather, for Spurgeon, God’s salvation was the reason for our singing. Singing was not just another thing to pass the time, more entertainment to indulge the senses. No, singing was an appropriate and responsive act of praise to the God who accomplished salvation for his people in Christ Jesus. Speaking to his congregants, Spurgeon exclaimed, “Ye children of his grace, sing unto your Father’s name, and magnify him who keeps you alive.” As a redeemed sinner, Spurgeon declared that “There is no song like that of redemption.” He insisted our God “must be extolled…and he must have the best of our songs.” Spurgeon noted, “Praise is the beauty of a Christian. What wings are to a bird, what fruit is to the tree, what the rose is to the thorn, that is praise to a child of God.”

Spurgeon regarded singing as an excellent exercise for internalizing the truths of Scripture. The Bible is a book “whose every leaf is of untold value” and whose “every promise will spring a sonnet.” Spurgeon said that “If we read it aright [Bible]” we might draw out of the Scriptures “matchless music such as no other instrument in the world could ever produce.” For, “The whole revelation of God is the condensed essence of praise.”

All Christians should aspire to store up the truths of the Bible in their soul. Working towards that end, Spurgeon saw singing as an aid in this endeavor. He said, “there is no teaching that is likely to be more useful than that which is accompanied by the right kind of singing.”

Spurgeon appreciated something that a lot of churches often overlook: the teaching function of right singing. Not only is it right to respond in praise to God with singing, but singing has the ability to imprint the message of God’s Word deep into our hearts. Those who carry God’s revelation in their hearts “have a springing well within their souls at all times.” Therefore, churches ought to be vigilant in deciding what they sing in their public gatherings.

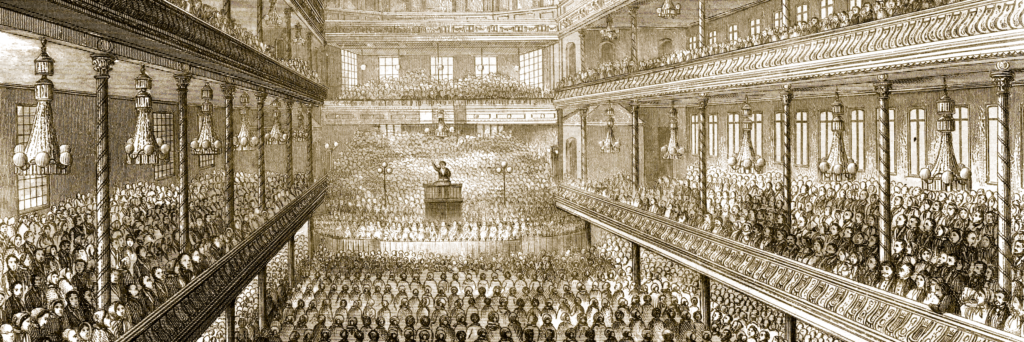

Lastly, Spurgeon saw congregational singing as a means of glorifying God and maintaining unity among the saints. He asserted that “the main object of our singing…must be the glory of God” and that singing was “the mark of a revived church everywhere.” Spurgeon thought that the joyous worship of God resulted in the singing of the saints. He believed our “master-passion” should be the “zeal of God’s house” which is expressed in our singing “heartily as unto the Lord; not with our voices only, but with our very souls.”

Spurgeon loved music and urged his parishioners to “Pull out the stops of your organ, and let the music fly abroad.” Since “Praise is the beauty of a Christian,” Spurgeon wanted his congregant’s praise to overflow and magnify the glory of the God who redeemed their souls. Thus he felt it his pastoral duty to guide and guard what the congregation sang. It is not only right but fitting that the communion of saints be steeped in true biblical doctrine as they direct their praises upward in a “sense of united adoration.”