Charles Spurgeon wore many hats. He was a husband, father, evangelist, author, abolitionist, editor, and college president. By 1884, he had founded sixty-six ministries in London: two orphanages, a clothing drive, a nursing home, a ministry to policeman, and dozens more. But Spurgeon is best remembered as a preacher. Helmut Thielicke said he combined two things: oxygen and grace (Encounter with Spurgeon, 19). His sermons had broad appeal. He spoke in the language of the working-class and packed his sermons with colorful imagery, sharp wit, and illustrations taken from ordinary life.

Spurgeon’s sermons were accessible and affordable – only one pence each. In Scotland, they were sold beside newspaper stands. His sermons were translated into over forty languages:

A Christian in China preferred to “go without a meal than miss this spiritual food” (The Sword and the Trowel, May 1884:246).

A criminal in Jamaica was last seen reading Spurgeon’s tract “Christ the Food of the Soul” just before his execution.

After about fifty or sixty British troops in India passed around Spurgeon’s sermon, they returned it “all black and fringed” (The Sword and the Trowel, October 1879:496).

In Australia, a convict escaped from prison and was converted after he read a “blood-stained” sermon looted from the pocket of his murdered victim.

D. L. Moody said, “It is a sight in Colorado on Sunday to see the miners come out of the bowels of the hills and gather in the schoolhouses or under the trees while some old English miner stands up and reads one of Charles Spurgeon’s sermons” (William R. Moody, The Life of Dwight L. Moody, 456).

Spurgeon’s sermons connected with readers in his day and in ours. But have you ever wondered how Spurgeon prepared his sermons? How much time did he allocate? Did he preach from manuscripts or outlines?

Here are six ways to prepare your sermons like Spurgeon:

1. Fiercely Protect Your Preparation Time.

Spurgeon was known for his hospitality and often entertained guests at his home. But on Saturday evenings at 6:00 p.m., Spurgeon dismissed his dinner companions, saying, “Now, dear friends, I must bid you ‘Good-bye,’ and turn you out of this study; you know what a number of chickens I have to scratch for, and I want to give them a good meal to-morrow” (Autobiography, 4:64).

Spurgeon didn’t require large blocks of time for sermon preparation, but he did protect the hours he allocated – even at the risk of being discourteous.

Feeding a flock always demands time in the kitchen.

2. Select Short Texts, Then Rotate.

Spurgeon did not preach sequentially through Scripture—few Victorians did. Instead, he believed God would provide him a fresh text every week.

“How shall I obtain the most proper text?” a student once asked him. “Cry to God for it!” Spurgeon replied (Lectures to My Students, 1:90). He practiced what he preached. He often abandoned his study in frustration, crying out for help. “Wifey, what shall I do? . . . God has not given me my text yet” (Autobiography, 4:65).

Susannah reflected:

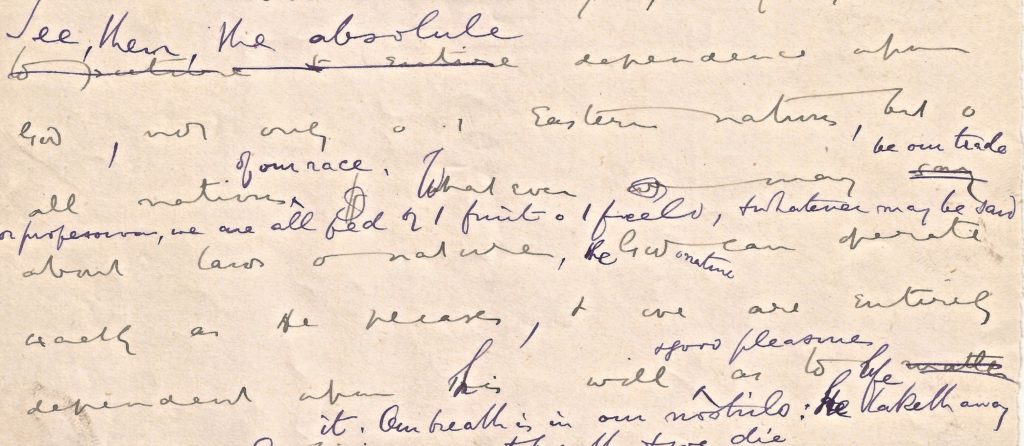

Sometimes, when I left him on Saturday evening, he did not know either of his texts for Sunday. But he had a well-stored mind; and when he saw his lines of thought, a few catchwords on a half-sheet of notepaper sufficed. Before we parted, he used to offer up a short prayer which was an inspiration to both of us (Autobiography, 4:274).

How did Spurgeon properly identify his text? Here’s his advice: “When a verse gives your mind a hearty grip, from which you cannot release yourself, you will need no further direction as to your proper theme” (Lectures to My Students, 1:88).

Spurgeon selected short texts, usually just a verse or two. He occasionally even preached from half a verse, or even two or three words (see his 1889 sermon on John 11:35, “Jesus Wept,” MTP 35, Sermon 2091).

Spurgeon’s goal was not to cover large swaths of Scripture in every sermon, though he did showcased all of Scripture in each verse. Instead, his goal was to draw out the spiritual nourishment in each bite-sized verse. And he did this masterfully (see his 1883 sermon on Job 6:6, “Is there any taste in the white of an egg?” in MTP 29, Sermon 1730).

Like a diamond when light passes through it, Spurgeon rotated the text to illuminate colorful shards of truth from every angle. He accomplished this by asking the text questions like Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How?

Spurgeon believed each word, each phrase, reveals fresh insights.

3. Write Manuscripts or Outlines . . . and Let Your Wife Help.

Once you’ve selected a text, produce a manuscript or outline. Spurgeon tried both at different seasons of his ministry.  In his earliest sermons (1851) Spurgeon preached from simple outlines or “skeletons,” as he called them. On the title page of Notebook 1 (1851), he wrote, “And only skeletons without the Holy Ghost.” But by 1854, his skeletons had morphed into twelve-to-fifteen-page sermons.

In his earliest sermons (1851) Spurgeon preached from simple outlines or “skeletons,” as he called them. On the title page of Notebook 1 (1851), he wrote, “And only skeletons without the Holy Ghost.” But by 1854, his skeletons had morphed into twelve-to-fifteen-page sermons.

Life got busy when Spurgeon moved to London and he reverted to preaching from outlines. Some he scribbled on envelopes. He said, “I believe that almost any Saturday in my life I make enough outlines of sermons, if I felt at liberty to preach them, to last me for a month” (Lectures to My Students, 1:88).

Susannah often helped her husband in his sermon preparation. She read Scripture to him aloud while he outlined the main divisions. On April 14, 1856, she helped him more than usual when her husband forgot to prepare his sermon. The night before, Susannah heard Charles preaching a sermon in his sleep on Psalm 110:8. She scribbled down his words and presented them to him on the next morning – and Charles preached from her notes (see “A Willing People and an Immutable Leader,” NPSP 2, Sermon 74).

4. Feed Sheep, Not Giraffes.

Spurgeon didn’t prepare for the first sermon he preached because he was tricked into preaching it. It was a defining moment for Spurgeon and every sermon thereafter was flavored by that experience.

Spurgeon’s preaching was conversational, extemporaneous, and “off the cuff.” He was forceful, winsome, direct, and earthy. He had no patience for the dry, polished lectures many preachers delivered from Victorian pulpits. Spurgeon criticized a sermon that “requires a dictionary rather than a Bible to explain it” (MTP 56:482).

His critics accused him of being irreverent and vulgar, but Spurgeon’s goal was not to impress ivory tower academics. “The Lord Jesus did not say, ‘Feed my giraffes,’ but ‘Feed my sheep’” (Spurgeon, The Salt-Cellars, 56).

Spurgeon’s formative years of ministry were spent in the fields of Cambridge, not in her colleges. Charles was a country preacher – and when he arrived in London he had the polka-dotted handkerchief to prove it (Susannah threw it away after they married). Spurgeon’s first congregation in Waterbeach were farmers. And so he learned to preach in a simply, direct way – characteristics he retained for the rest of his ministry.

Spurgeon mastered a form of communication championed in our own day – saying more with less. No wonder he dominates the Twitterverse. Spurgeon doesn’t need 140 characters to get the gospel across.

The preacher must also mind that he preaches Christ very simply. He must break up his big words and long sentences, and pray against the temptation to use them. It is usually the short, dagger-like sentence that does the work best. . . . He must employ a simple, homely style, or such a style as God has given him; and he must preach Christ so plainly that his hearers can not only understand him, but that they cannot misunderstand him even if they try to do so (MTP 56:489).

5. Have the Humility to Consult Commentaries.

Spurgeon had enough humility to know that he didn’t know everything. In fact, what he did know had been known before.

Spurgeon’s earliest ministry was shaped by reading preachers. Commentaries and books on sermon preparation were only an arms-length away. Here are a few of Spurgeon’s go-to grabs:

- John Calvin’s Commentaries

- Jean Claude’s Essay on the Composition of a Sermon

- John Gill’s A Body of Doctrinal Divinity and An Exposition of the Old and New Testament

- Charles Simeon’s Horae Homileticae and Six Hundred Skeletons of Sermons

- Matthew Henry’s An Exposition of the Whole Bible

Spurgeon also consulted John Bunyan, Jeremiah Burroughs, Thomas Manton, John Flavel, Richard Baxter, Philip Doddridge, George Whitefield, John Stephenson, Andrew Bonar, Andrew Fuller, Jonathan Edwards, and dozens more. Spurgeon even published a book about the value of commentaries (see Commenting on Commentaries).

The past had something significant to teach the present about how to move into the future. Spurgeon understood that he didn’t have to reinvent the wheel of preaching – he simply needed to put his own spin on it for a new generation.

6. Preach Jesus Christ.

In virtually all of his sermons, Spurgeon zig-zagged his way to Jesus Christ. Influenced by the Puritans, Spurgeon’s route to the cross often employed typology, allegory, spiritualizing, and metaphor.

But he warned his students against the abuses and excesses of these devises. He criticized Benjamin Keach for running away with his metaphors “not only on all-fours, but on as many legs as a centipede” (Lectures to My Students, 1:109). John Bunyan got more grace from Spurgeon because, after all, he was “the chief, and head, and lord of all allegorists . . . . He was a swimmer, we are but mere waders” (Lectures to My Students, 1:116).

Yet every sermon must take the listener to the cross:

But what is the Scripture’s great theme? Is it not, first and foremost, concerning Christ Jesus? Take thou this Book, and distill it into one word, and that one word will be Jesus . . . and we may look upon all its pages as the swaddling bands of the infant Saviour; for if we unroll the Scripture, we come upon Jesus Christ himself (MTP 57:496).

Spurgeon once said, “If a man can preach one sermon without mentioning Christ’s name in it, it ought to be his last” (MTP 13:489).